Three years on, Ukraine’s extinction nightmare has returned

By Spurb Ernest

Kyiv no longer looks like a city at war in the way that it was three years ago. The shops are open and commuters get delayed in traffic jams on their way to work. But in the days since 12 February this year when US President Donald Trump rang Russia’s Vladimir Putin to send a 90-minute political embrace from the White House to the Kremlin, 2022’s old nightmares of national extinction have returned. Ukrainians used to get angry about the way that President Joe Biden held back weapons systems and restricted the way Ukraine used the ones that arrived here. Even so, they knew whose side he was on.

Instead, Donald Trump has delivered a stream of exaggeration, half-truths and outright lies about the war that echo the views of President Putin. They include his dismissal of Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky as a dictator who does not deserve a seat at the table when America and Russia decide the future of his country. The biggest lie Trump has told is that Ukraine started the war.

Trump’s negotiating strategy is to offer concessions even before serious talks have started. Instead of putting pressure on the country that broke international law by invading its neighbour, leading to huge destruction and hundreds of thousands of dead and wounded, he has turned on Ukraine.

His public statements have offered Russia important concessions, declaring that Ukraine will not join Nato and accepting that it will keep at least some of the land it seized by force. Vladimir Putin’s record shows he respects strength. He regards concessions as a sign of weakness.

He has not budged from a demand for even more Ukrainian land than his men now occupy. Immediately after the first talks, held in Saudi Arabia, between Russia and the US since the 2022 invasion, Putin’s foreign minister Sergei Lavrov repeated his demand that no Nato troops would be allowed into Ukraine to provide security guarantees.

A veteran European diplomat who has dealt with the Russians and the Americans told me that when the grizzled, highly experienced Lavrov met Trump’s novice Secretary of State Marco Rubio “he would have eaten him like a soft-boiled egg.”

Challenging times

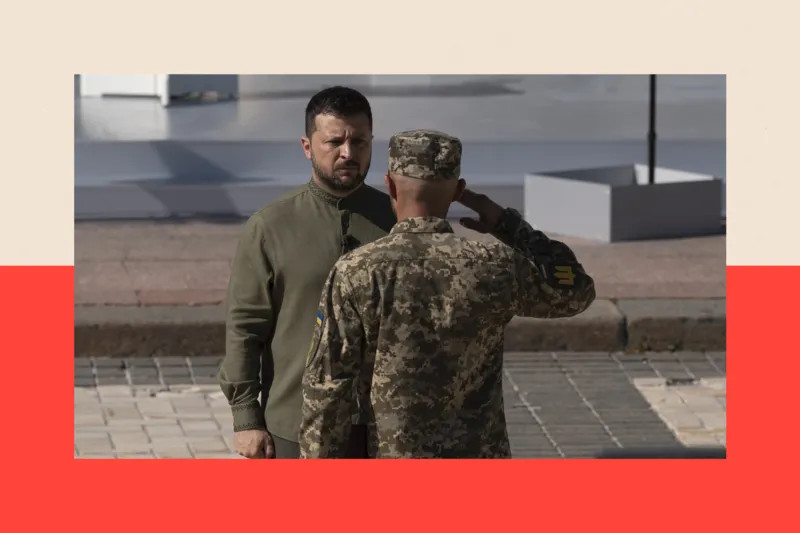

A few days ago, as Trump threw more insults at Ukraine’s president, I went to the heavily guarded government quarter in Kyiv to meet Ihor Brusylo, who is a senior adviser to Volodymyr Zelensky and deputy head of his office. Brusylo acknowledged how much pressure Trump is putting on them.

“It’s very, very tough. These are very hard, challenging times,” Brusylo said. “I wouldn’t say that now it’s easier than it was in 2022. It’s like you live it all over again.”

Brusylo said Ukrainians, and their president, were as determined to fight to stay independent as they had been in 2022.

“We’re a sovereign country. We are part of Europe, and we will remain so.”

Fading colours

In the weeks after Vladimir Putin ordered the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the sound of battle on the edge of Kyiv echoed around streets that were almost empty. Checkpoints and barricades, walls of sandbags and tank traps welded from steel girders were rushed out onto Kyiv’s broad boulevards. At the railway station, fifty thousand civilians a day, mostly women and children, were boarding trains going west, away from the Russians.

The platforms were packed and every time a train pulled in, came another surge of panic as people pushed and shoved to get on. In those freezing days, in bitter wind and flurries of snow, it felt as if the colours of the 21st century were fading into an old monochrome newsreel that Europeans had believed until then was safely consigned to the vaults of history.

President Zelensky, in Joe Biden’s words, “didn’t want to hear” American warnings that an invasion was imminent. Putin rattling a Russian sabre was one thing. A full-scale invasion, with tens of thousands of troops and columns of armour, surely belonged in the past.

Putin believed Russia’s mighty and modernised army would make quick work of its obstinate, independent neighbour and its recalcitrant president. Ukraine’s western allies also thought Russia would win quickly. On television news channels, retired generals talked about smuggling in light weapons to arm an insurgency while the west imposed sanctions and hoped for the best.

As Russian troops massed on Ukraine’s borders, Germany delivered 5,000 ballistic combat helmets instead of offensive weapons. Vitali Klitschko, the mayor of Kyiv and once heavyweight boxing champion of the world, complained to a German newspaper that it was “a joke… What kind of support will Germany send next, pillows?”

Zelensky turned down any idea of leaving his capital to form a government in exile. He abandoned his presidential dark suit for military attire, and in videos and on social media told Ukrainians he would fight alongside them.

Ukraine defeated the Russian thrust towards the capital. Once the Ukrainians had demonstrated that they could fight well, the attitude of the Americans and Europeans changed. Arms supplies increased.

“Putin’s mistake was that he prepared for a parade not a war” a senior Ukrainian official recalled, speaking on condition of anonymity. “He didn’t think Ukraine would fight. He thought they would be welcomed with speeches and flowers.”

On 29 March 2022, the Russians retreated from Kyiv. Hours after they left, we drove, nervously, into the chaotic, damaged landscape of Kyiv’s satellite towns, Irpin, Bucha and Hostomel. On the roads the Russians had hoped to use for a triumphant entry into Kyiv, I saw bodies of civilians left where they were killed. Charred tyres were stacked around some of them, failed attempts to burn the evidence of war crimes.

Survivors spoke of the brutality of the Russian occupiers. A woman showed me the grave where she had buried her son single-handed after he was casually shot dead as he crossed a road. Russian soldiers threw her out of her house. In the garden, they left piles of empty bottles of vodka, whisky and gin that they had looted and drunk. Hastily abandoned Russian encampments in the forests near the roads were choked with rubbish their soldiers had discarded over the weeks of occupation.

Professional, disciplined armies do not eat and sleep next to rotting piles of their own refuse.

Three years on, the war has changed. Although Kyiv has revived, it still has nightly alerts as its air defences detect incoming Russian missiles and drones. The war is closer, and more deadly, along the front line, more than 1,000 kilometres long, that runs from the northern border with Russia and then east and south down to the Black Sea. It is lined with destroyed, almost deserted villages and towns. To the east, in what was Kyiv’s industrial heartland of Donetsk and Luhansk, Russian forces grind forward slowly, at a huge cost in men and machines.

Echoes of the past

Last August, Ukraine sent troops into Russia, capturing a pocket of land across the border in Kursk. They are still there, fighting for land that Zelensky hopes to use as a bargaining chip.

Along the border with Kursk, in the snow-covered forests of north-eastern Ukraine, the geopolitical storm set off by Donald Trump is still not much more than a menacing, distant rumble. It will get here, especially if the US president follows up his harsh and mocking verbal attacks on president Zelensky with a final end to military aid and intelligence-sharing, and even worse from Ukraine’s perspective, an attempt to impose a peace deal that favours Russia.

For now, the rhythm built up in three years of war goes on, and the forest could be a throwback to the blood-soaked twentieth century. Fighting men move silently through the trees, along trenches and into bunkers dug deep into the frozen earth. In stretches of open ground, anti-tank defences made of concrete and steel stud the fields.

The 21st century is more present in the dry and warm underground bunkers. Generators and solar panels power laptops and screens linked to the outside world, and bring in the news feeds.